The strange landscape of DAO legal structures recently acquired a permutation of the DAO LLC: the Decentralized Unincorporated Non-Profit Association or DUNA.

In what follows, we're doing a deep dive and weigh its pros and contras.

The State of Entitylessness

DAOs generally either do not make use of a legal entity (an “entityless” structure) or they adopt an ownerless foreign foundation structure.

The entityless structure leaves all three of the key issues facing DAOs unresolved:

- No recognized legal existence.

- Potential tax liabilities as a result of its inability to pay taxes.

- Lack of limited liability.

As a result, many decentralized projects have wrapped themselves in a foreign foundation legal skin, most typically in the Cayman Islands which allows for "founderless" foundations.

However, despite addressing the three shortcomings of entitylessness above, the Cayman founderless foundation comes with its own set of issues, including that:

- It requires real-world human control, which limits the extent to which a DAO can be truly trustless and decentralized;

- It is rather complicated to govern, and is costly and non-trivial to set up;

- It subjects the DAO to uncertain tax treatment and could ultimately be challenged by many different jurisdictions.

Do the DUNA

Aiming to address the above shortcomings, and driven by clear impetus from corners of the U.S. venture capital community - who had invested in projects with foreign foundations, which have unclear tax and reporting treatment - Wyoming signed the DUNA into law on 7 March of this year, with it taking effect on 1 July 2024.

In what follows, we dissect key aspects of the DUNA, particularly in comparison to a foreign foundation.

Benefits

- Decentralization: The DUNA supports decentralization: there is no need for a traditional corporate-type hierarchy (most importantly directors), and governance can be fully on-chain, without ongoing real-world human activity.

- Administrators with limited authorization to perform specific tasks authorized by the membership can be selected.

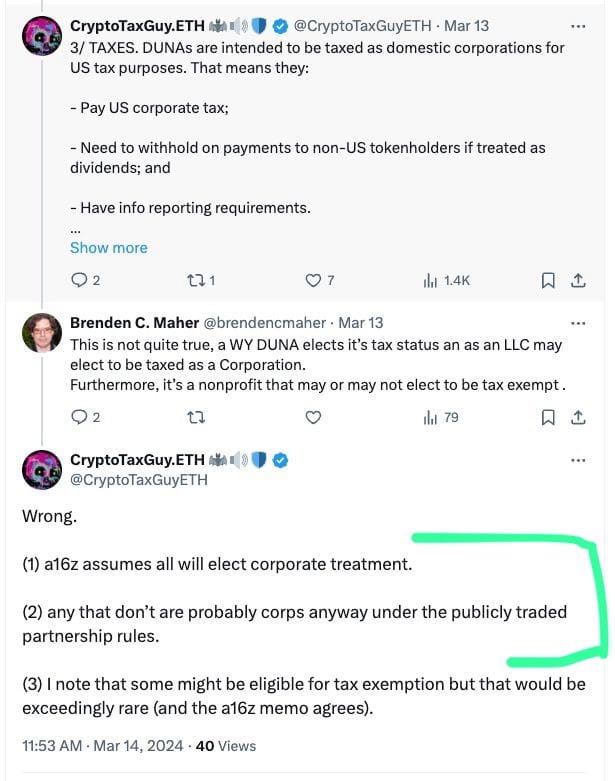

- Taxation: The DUNA can elect to pay a 21% corporate tax on profits.

- This contrasts with the much more opaque tax treatment of foreign foundations (for a much more detailed discussion of the potentially vast risks/liabilities facing foreign foundations with U.S. links, see Part II of A16Z's examination of DAO structures).

- There is, however, still a lot of nuance around the taxation of DUNAs given their recent inception (see below).

- Profit Generation: Its status as a non-profit does not preclude a DUNA from generating profits, but does impose limitations on profit distributions (see below).

- Filing & Complexity: There is no mandatory filing for a DUNA, so setting one up can be fast, simple and cheap, as there is no requirement for registration with Wyoming Registry. This also means less dependency on specialized advisers/counsel.

- However, some (potentially legal) complexity may arise in defining roles and responsibilities, particularly around administrator authority.

- This is the flip side to having complete flexibility – an almost blank slate means fewer defaults to fall back on.

- Stability, Certainty & Regulation: Some argue that because the DUNA is U.S.-based, it is less likely to face aggressive regulation or censorship (compared to foreign foundations), although this is debatable in light of the SEC's regulation by enforcement, and high-profile DAOs offering a token in the U.S. could still attract regulatory scrutiny. Nevertheless, it is certainly true that is easier for U.S.-based entities to take investment from, and to employ, U.S. citizens/institutions vs. foreign foundations.

- Flexibility & Control: The DUNA is maximally flexible, and its governance can be defined entirely by "governing principles" agreed by members. The Wyoming DUNA Act ("WDUNAA") also directly recognizes smart contracts and other agreed-upon blockchain-based governance proposals as binding.

- Transferability: Except as otherwise provided in the DUNA's governing principles, a member interest or any right thereunder is freely transferable to another person through the conveyance of the membership interest or other property that confers upon a person a voting right within the nonprofit association.

- Liability Limitation: Liability protections can extend to purely on-chain governance actions and do not require a board, as discussed in more detail below. However, the effectiveness of these liability protections is still largely untested.

- Member Anonymity: The DUNA is expected to avoid the Corporate Transparency Act of 2024 ("CTA") as there is no requirement for filing with Wyoming's Secretary of State (but again this is nuanced, especially when the DUNA wants to access regulated services). Additionally, it is expected that, as a U.S.-based entity, the DUNA will be far less vulnerable to geopolitical risks as compared to a foreign foundation in, for example, the Cayman Islands, which faces persistent pushback from E.U. Anti-Money Laundering and FATF regulations.

- Tax-Exemption: DUNAs are eligible to attain tax-exempt status depending on their activities (must fall within e.g. 501(c)).

Flaws

- Member Requirement: The DUNA requires a minimum of 100 members for formation and continued operation (which could be a significant hurdle for smaller DAOs, particularly those just starting out). Since token holders = members, this would mean a DAO token would need to exist AND be sufficiently distributed before a DUNA could be formed.

- Profit Distribution: There are limitations on the ability to distribute profits to members (e.g. dividends are not permitted), although 'reasonable' compensation can be paid to members and administrators (e.g. for services provided, including 'governance'). However ultimately, for DAOs not otherwise prohibited from profit distributions under U.S. securities law, the DUNA may be overly restrictive.

- Further, member distributions of profits would invalidate the protections of the DUNA if they were to exceed what was allowable under the law.

- It is unclear to what extent "reasonable compensation" could be stretched - perhaps an argument could be made that it is justifiable to increase compensation for governance when the DUNA performs well (i.e. makes greater profits), as the governance decisions have led to those profits? However ultimately, this will still act as a limitation in certain cases.

- Tax Optimization: a DUNA is generally not tax-optimized compared to a foreign foundation. On the flip-side, a DUNA's tax treatment reduces tax risk and uncertainty, and is far simpler.

- 'Dividend' Tax: Whilst paying members for "governance" may constitute compensation for the purposes of the WDUNAA, it doesn't seem that this would be compensation for US tax purposes, meaning that it would be considered a dividend. Token buybacks would also be dividends for US tax purposes unless they meaningfully reduce a tokenholder's interest in the DAO. Additionally, the DUNA would have to withhold 30% on dividends to non-resident aliens (and report dividends on IRS Form 1099-DIV & Form 1042), so it has to KYC 'dividend' recipients (businesses are typically required to issue a 1099 form to a taxpayer (other than a corporation) who has received at least $600 USD or more in non-employment income during the tax year).

- (Note that there is a potential reduction from 30% to 15% for EU residents willing to provide tax forms)

- Member Anonymity: As discussed above, a DUNA might have to collect tax forms to comply with tax reporting on IRS Forms 1099-DIV & 1042. Foreign corporations don't have the same info reporting requirements. Issues may also arise in relation to Form 5472 & Form 1120 Schedule G (requirements to report on certain large direct or indirect holders) - although foreign corporations may have to complete these too. A DAO may decide that the extra tax incurred in operating as a foreign foundation is a worthwhile cost to pay to avoid doxxing members.

- Recognition: There is a risk of the DUNA not being recognised by other states, though much of this risk can be mitigated through contractual protections.

- Censorship Resistance: DUNAs may offer better resistance to censorship within the U.S., but could still attract regulatory scrutiny if perceived as engaging in risky activities.

Who needs a DUNA?

- DAOs with at least 100 members (token holders) can declare themselves DUNAs under the new Wyoming DUNA Act, without the need to file with the state of Wyoming. As a result, while remaining "unincorporated", they still benefit from limited liability and, depending on their tax election, a more predictable (though still untested) tax regime for the DUNA's income and its members compared to entityless DAOs.

- A DUNA may be most suitable for network and protocol DAOs with significant U.S. ties, including sub-DAOs thereof.

- Additionally, non- investment and non-LCA (Limited Cooperative Association) DAOs with significant U.S. ties, such as social DAOs and collector DAOs, may benefit from a DUNA legal skin.

Further analysis. Warning: Anoraks only!

In what follows, we do a deep dive on DAO legal structures including the DUNA, borrowing heavily from - but also commenting on - A16Z's "The DUNA: An Oasis for DAOs" and the 3-part "Legal Framework for DAOs" guide it commissioned on the subject (Part I, Part II and Part III).

America first: The significance of "US links"

In our view, the first filter when deciding whether to remain entityless as a DAO or adopt a legal skin is whether the DAO has significant U.S. membership.

Having significant U.S. membership in a DAO limits the feasibility of foreign trust structures and foreign incorporated structures, such as foreign foundations, as these foreign entities trigger heavy reporting requirements and potentially unfavorable tax treatment for U.S. members.

One DAO wrapper - the Republic of the Marshall Islands' "DAO LLC" ("RMI DAO LLC") - may have the closest similarity to the DUNA. However, under U.S. taxation such an entity is generally treated as a Foreign Corporation (unless approved for tax-exempt status within the United States).

This, together with part of the U.S. venture capital community seeking "respectability" for its DAO portfolio projects with significant US members by seeking to give them a clearer tax and reporting treatment, largely explains the emergence of the DUNA in what many consider a jurisdiction "one can work with": Wyoming.

The "D" in DUNA...

As noted earlier, high on the list of desirable properties for a U.S.-centric DAO legal skin was its ability to support decentralization, which means that it does not require traditional hierarchical elements like officers or boards of directors.

This makes DUNAs suitable for truly decentralized organizations, which - with a wink to the Howey test - are not controlled by a person or an affiliated group of persons, i.e. organizations whose success or failure does not depend solely on the managerial efforts of any person or affiliated group of persons.

As a result, the DUNA contemplates a baseline structure that does not include a management function, but instead allows for the selection of "administrators" with limited authorization to perform specific tasks authorized by the membership.

This categorization aligns the Model DUNAA (Decentralised Unincorporated Nonprofit Association Act) with applicable standards for decentralization under U.S. securities laws.

...vs. the "F" in Foundation

By contrast, foreign foundations, even in the Cayman Islands where they can be formed without a named founder, still need to designate an individual as the controller/contact/responsible person for the entity (in the absence of a single Ultimate Beneficial Owner).

Moreover, recent changes in Cayman's Beneficial Ownership regime now require such individual's details to appear on the Cayman Corporate Registry. Whilst this registry is nott publicly accessible, it is safe to assume that such details will be shared with law enforcement and government agencies, thereby greatly diminishing the anonymity of the Cayman Foundation.

Finally, in order to provide limited liability protection to a DAO, the structure of a foreign foundation requires off-chain actions to be taken by individuals (e.g., enforcers, foundation directors or trustees) at the direction of the DAO, typically by way of an on-chain vote.

This means that even though DAO members are not actual members (or owners) of the foreign foundation, and limitations on the level of trust placed in its board can be included in its organizational documents, the relationship between the DAO and the foreign foundation can never be entirely trustless, This reliance on a board or other off-chain entities may compromise the DAO’s decentralization.

In practice

Practically, foreign foundations, because of their nature and offshore residency, face difficulties in becoming fully operational in their own right, e.g. by establishing a workforce to run the project from within the foundation itself.

This risks making them overly dependent on the developer company (typically a C-Corp for U.S.-based teams) and compromising their degree of decentralization, in addition to potentially dragging the entire foreign structure into the U.S. regulatory and tax web.

Irrespective of the above, and the various ways of mitigating these issues, the legal requirement for a foreign foundation (whether Cayman or elsewhere) to have an appointed Director inherently prevents it from being a purely decentralized setup.

P as in "Profit"

When the DUNA first came on the scene, many Web3 builders gasped at its not-for-profit nature.

However, a DUNA is not limited in its ability to generate profits; its "non-profit" status simply prevents it from paying dividends or making distributions to members (except for those permitted by statutes).

For instance, under the WDUNAA, a DUNA may

pay reasonable compensation or reimbursements of reasonable expenses to its members, administrators and persons outside the nonprofit association for services rendered, including with respect to the administration and operation of the nonprofit association, which may include the provisions of collateral for the self-insurance of the nonprofit association, voting or participation in the nonprofit association's operations and activities' (if doing so is authorized by the governing principles).

A DUNA may also

[...] confer benefits on its members or administrators in conformity with its common non-profit purpose; repurchase membership interests (to the extent authorized by the nonprofit association's governing principles); and make distributions of property to members upon winding up and termination of the decentralized unincorporated nonprofit association [...].

What a DUNA cannot do is straight dividending, i.e. granting its members the right to share in its profits or distributing profits in a manner analogous to equity distribution mechanisms.

Offending Gary

Network and protocol DAOs should avoid mimicking traditional equity structures, as doing so could blur the distinction between governance tokens and securities, thereby offending both Gary (Gensler) and the IRS.

Instead, DAOs should focus on tokenomics that incentivize productive contributions, such as governance participation, staking, and capital contributions, which drive the long-term value of the network.

This approach aligns with the decentralized, participant-driven ethos of web3, optimizing value across the ecosystem, rather than prioritizing short-term profits.

The L in Limited Liability

Although the DUNA structure is relatively untested, existing case law on UNAs is instructive regarding the effectiveness of limited liability for decision-making members, and the WDUNAA explicitly affirms that a DUNA is a separate legal entity from its members.

- Debts and obligations: Upon formation, members and administrators of a DUNA are granted limited liability for the DUNA’s debts and obligations. They are only personally liable for their own tortious acts, or if they personally guarantee a contract or fail to disclose their role as an agent for the DUNA. Otherwise, members and administrators are not liable for the DUNA’s tort or contract liabilities. Creditors can only pursue the DUNA’s assets to satisfy judgments, not the personal assets of its members or administrators. (However, there is one exception: under the alter ego or veil piercing doctrine, the DUNA’s separate legal status could be disregarded, making the personal assets of members and administrators accessible to satisfy the DUNA’s debts).

- A DUNA can sue or be sued in its own name, with legal actions able to be initiated against its registered agent or as otherwise provided by law.

"A" as in Administration...

Informal formation: DUNAs (like UNAs) are informal, with minimal administrative complexity and no mandatory filings with the Secretary of State (although there are optional filings), allowing operations with little oversight. Further, the limited case law on UNAs specifically contemplates the lack of formality of the members not being grounds for disregarding the entity's legal status.

Information rights: DUNA members and administrators have the right to inspect the association’s books and records, but since there is no requirement to maintain specific records (including member listings). Therefore, the information rights only apply to whatever records the association has chosen to maintain. If records are kept on distributed ledger technology accessible to members and administrators, such information rights should be easily met. Former members and administrators retain the right to access information they were entitled to during their involvement, though some restrictions on access and use may apply.

... and as in Anonymity

While many jurisdictions do not require domestic entities to publicly list memberships, they often still demand that legal entities collect certain information for compliance and tax reporting. For DAOs prioritizing member anonymity, this is crucial when selecting an entity structure.

Failure to comply with the formalities required for any entity structure can result in losing the key benefits associated with that entity, such as limited liability. For example, DAOs using LLCs are often required to maintain member records. While some jurisdictions do not mandate public disclosure of these records, if member records are required at the entity level, it could compromise the anonymity of members and limit the effectiveness of these structures as liability protection vehicles. Wyoming and Tennessee’s DAO laws offer some improvement by not explicitly requiring member listing disclosures, but it’s unclear whether these laws fully exclude the listing requirements typically associated with LLCs. Additionally, the legal framework has not fully addressed how decentralized organizations, where no one has access to membership information, would manage or waive such requirements, even with notice in the articles of incorporation.

The Corporate Transparency Act (CTA) now requires disclosure to FinCEN of all beneficial owners ("BO") upon registration of an entity, and of all members who own 25% or more of the entity on an ongoing basis.

- The CTA's requirement to report all individuals that are beneficial owners upon its registration would be impractical and undesirable, especially given that a DUNA requires a minimum of 100 members to be validly formed.

- The operational word here is registration: as a result of how they are formed, without the need for any filing at Wyoming State Registry, DUNAs are expected to avoid the CTA requirements (in the same way a Series LLC that has been formed without filing, e.g. in the case of OtoCo's onchain Series LLCs) are not subject to the BO reporting). In addition, UNAs and DUNAs were explicitly excluded from Customer Due Diligence final rules of financial institutions, on which the CTA is largely based.

- Even though a DAO is unlikely to have members meeting the 25% threshold on an ongoing basis, entities to which the CTA applies (such as LLCs, LCAs, and Foreign Foundations registered to do business in the U.S.) generally must still be able to demonstrate that a sufficiently robust process is in place to evaluate ownership/control levels. For DAOs that utilize flow-through taxation structures (e.g in the form of an LLC under the default pass-through tax election), complying with the CTA would be relatively straightforward, as the information necessary for the CTA would already have been provided to file the tax returns. However, for DAOs wishing to maintain member anonymity, compliance may not be possible as an LLC or LCA.

As mentioned before (under 'Divided Tax'), issues may arise for DUNAs in relation to member anonymity when compensating members for their governance contributions.

"T" as in Transferability...

- Except as otherwise provided in the DUNA's governing principles, a member interest or any right thereunder is freely transferable to another person through conveyance of the membership interest or other property that confers upon a person a voting right within the nonprofit association.

- Many DAOs use their native token as proof of membership and as a tool for participating in governance decisions. Therefore, it is crucial for DAOs to consider whether an entity structure allows membership to be transferred simply by transferring the DAO’s native token or if it requires more formal processes for membership transferability.

- Although unrestricted transferability is often desirable, DAOs must also consider whether it could conflict with entity formality requirements or regulatory compliance. For instance, depending on the facts and circumstances of how a DAO organized as an LCA or LLC utilizes its tokens, an examination as to whether the tokens were effectively bearer shares may be necessary. Transparent Incorporation Practices in the U.S. Code prohibit "a corporation, limited liability company, or other similar entity formed under the laws of a State" [...] from "issue[ing] a certificate in bearer form evidencing either a whole or fractional interest in the entity".

...and as in Tax

The ease of compliance with applicable tax reporting and payment obligations varies hugely based on the DAO’s activities.

For DAOs using domestic U.S. entities such as the recently introduced DUNA, or the LLC, the tax reporting and payment requirements are quite clearly defined, and any complexity as to their treatment can be removed by electing corporate tax status, allowing entity-level taxation (see more on this below).

By contrast, DAOs with significant U.S. membership that opt for a foreign structure, such as an offshore foundation, may face more complex and potentially less advantageous tax obligations than they might initially anticipate.

Specifically, in relation to offshore foundations, there is uncertainty regarding how U.S. tax laws will ultimately treat them. If the IRS deems a DAO’s methods of directing foreign foundation directors to be leading to a mischaracterization, it may bring the DAO into the U.S. tax net, with potentially significant consequences.

The Appendix B of A16Z's second part DAO Legal Framework has a useful overview table for a number of DAO legal skins.

Elect to be taxed

Entity-level taxation is an option for several of those DAO legal skins, including domestic U.S. entities such as the DUNA or the LLC.

Such election may be particularly valuable when flow-through taxation is administratively infeasible, mainly due to U.S. members of a flow-through organization being responsible for annual income reporting, whether or not distributions were made, but also because of desired anonymity by DAO members.

While a U.S. entity electing corporate tax treatment would face a 21% federal tax rate on profits, it simplifies reporting and payment obligations for individual members, limiting them to specific payments, transfers over $10,000, and distributions, if any.

Moreover, tax benefits from treaties are easier to manage at the entity level, avoiding the complexities of passing them through to members, which would require individual filings and varied withholding rates.

Further optimization

Tax-free jurisdictions offer significant benefits when offshoring internet-only activities away from the United States.

However, the presence of U.S. members contributing value to income-producing activities and exercising collective operational control diminishes the effectiveness of such offshoring strategies.

If a protocol is fully functional and independent of updates, maintenance, or support, using an offshore entity could allow tax optimization. However, without the specific and limited circumstances that would make this strategy applicable to DAOs, this strategy could be less optimized than U.S. corporate tax rates and expose the structure to scrutiny by other tax authorities.

For DAOs with significant U.S. membership, the benefits of foreign trust structures and foreign corporate structures are largely negated by laws designed to prevent U.S. citizens from using foreign entities to avoid taxes. Foreign trusts, for example, risk being classified as foreign grantor trusts if U.S. citizens exert control over the trust’s funding. This classification can trigger tax obligations on the initial transfer and make the grantors responsible for ongoing tax liabilities of the trust.

A DUNA may therefore present itself as an appropriate tax alternative to offshoring where tokenholders (a) conduct substantial business activities (not including voting) on behalf of the DAO from within the United States, or (b) expect US law, not code, to govern disputes.

The analysis runs as follows:

- US tax law views a joint venture ("JV") for profit as an entity, even absent a legal entity. While some DAOs (e.g., big protocol DAOs) might be viewed as parameter selectors, not JVs, this argument probably won't work if someone is conducting business on the DAO's behalf.

- Once the DAO is seen as an entity, you should ask whether it is in a "U.S. trade or business" ("USTB"). This means that U.S.-based profit-making activity is regularly conducted (profit-making activity does not include voting).

- Non-US corporations are typically subject to 44.7% US tax on net income which is connected to a USTB. This contrasts with the 21% corporation tax (with an additional 30% tax on the remainder being imposed through withholding - only on foreigners and only when the corporation pays dividends) that U.S. corporations are subject to.

- Therefore, if a DAO is a tax entity, and most of its income is connected to a USTB, a U.S. corporation should generally yield a lower tax bill than a non-US corporation.

- Regardless, if members want U.S. law (as opposed to foreign law/code) to govern, then the deemed tax entity generally defaults to domestic.

Despite the above, there may still be good tax reasons not to use a DUNA, for example:

- If only some income is connected to a USTB, then a foreign corporation (e.g., a Cayman Foundation or a BVI entity) would be subject to U.S. taxes only on that income, not its entire income. Typically it will be best to block UTSB income within a US subsidiary.

- A DUNA may have to collect tax forms in order to comply with information reporting. However, foreign corporations don't have the same information reporting requirements. DAOs might decide that it is worth the extra tax to avoid doxxing its members.

- If members are U.S. and doxxed, a tax partnership might make more sense rather than a DUNA. This is because partnerships don't pay entity-level tax, instead partners are taxed on the DAO's income on a pass-through basis. Members may prefer a more traditional entity like an LLC to house a tax partnership.

- Finally, a DUNA can apply to become a 501(c) tax-exempt organization e.g. a 501(c)(3) charitable foundation, in which case donations to its cause will be exempt from U.S. tax.

Note that the above is based narrowly on tax considerations and does not take into account other factors. Also note that, specifically in relation to DUNAs making the tax partnership election, there is no precedent with the IRS or tax courts, and neither is there unanimity between practitioners, including those who have been privy to the creation of the WDUNAA itself!

Conclusion: The plot thickens

As DAOs continue to push the boundaries of decentralized governance, the DUNA presents itself as a compelling middle ground between the freewheeling world of entityless structures and the rigid frameworks of traditional corporations.

It offers a path for DAOs to gain legal recognition, limited liability, and a more predictable tax regime - all while retaining their decentralized governance.

However, as with any sequel, the plot thickens. The DUNA comes with its own set of challenges, particularly around member requirements, profit distribution, and potential regulatory scrutiny. For some DAOs, it might be the perfect fit - offering just enough structure to keep regulatory retaliation at bay without stifling innovation. For others, especially those with complex international operations or a preference for anonymity, a foreign foundation might still be the safer bet (even if it means paying a little more in taxes if the DAO has U.S.-connected income and/or running the risk of being dragged into the U.S. tax net if there are U.S.-based DAO members who are involved with the DAO beyond mere voting).

In the end, choosing whether to get into the all-American hero DUNA skin or don the dark cape of a foreign setup comes down to the specific needs and goals of your DAO. If you’re looking to operate within the U.S., take investments from the U.S., or want more legal and tax certainty, the DUNA could be your superhero costume. This also explains why the DUNA has been promoted quite hard by corners of the U.S. venture capital industry who in the token heydays funded a lot of DAO projects without a proper setup, and who'd like to see a lot of offshore projects repatriated to the U.S.

However, as with any superhero movie, taking the role of a DAO comes with challenges and struggles and there are no guarantees of a happy ending.

So, whether you’re ready to embrace the DUNA or still debating whether this latest sequel is worth the watch, one thing is clear: the world of DAO legal structures is anything but boring, and there’s plenty more drama to come. Stay tuned!

>> Book a call with Otonomos to weigh your options if you're a DAO.

With special thanks to Conall Fowler, Summer 2024 intern at Otonomos.